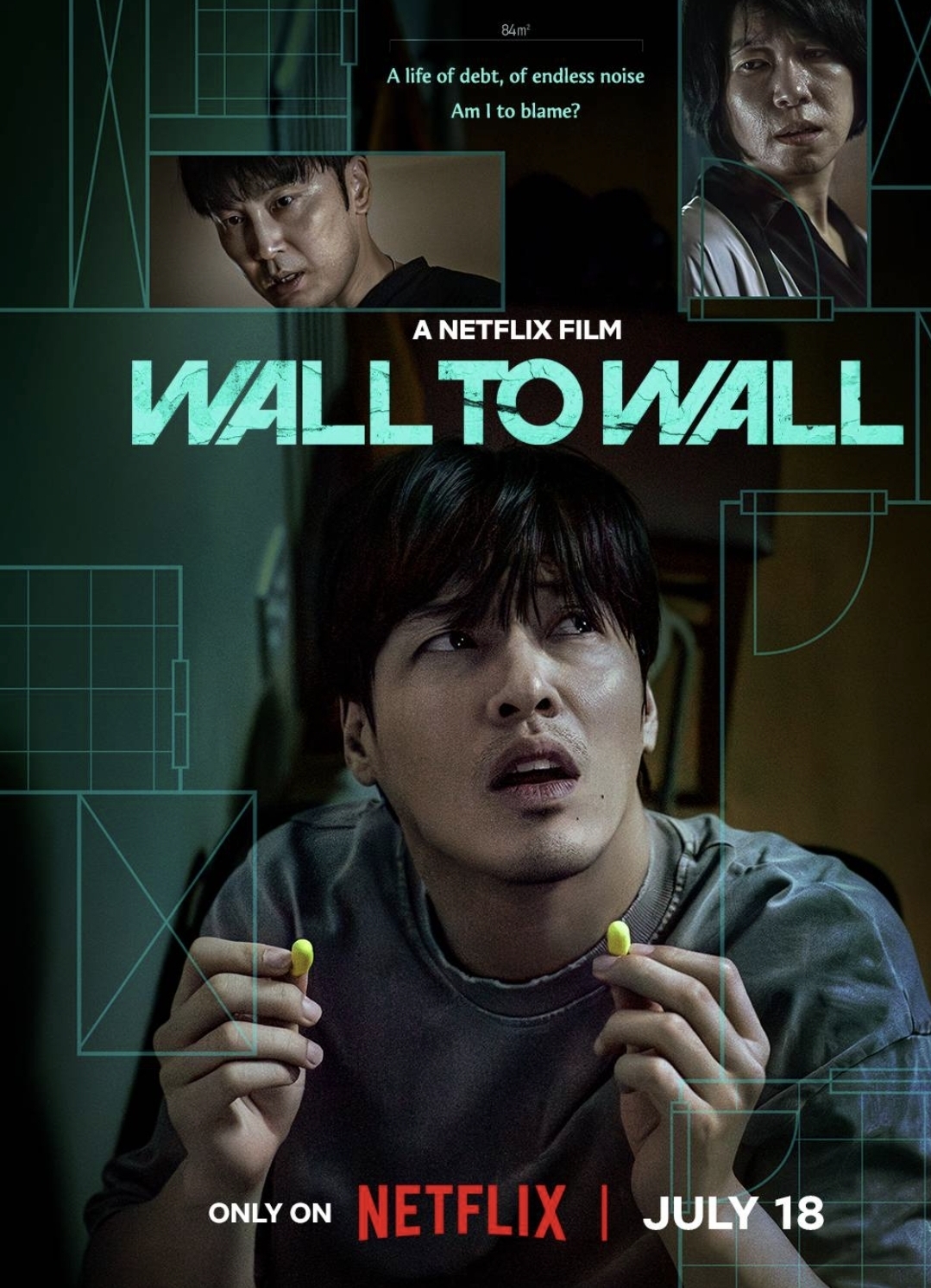

Director: Kim Tae-joon

Starring: Kang Ha-neul, Seo, Hyun-woo, Yeom Hye-ran

Country of Origin: South Korea

Running time: 1h 58m

In the densely packed apartment villages of Seoul silence is a valuable commodity.

There’s no escaping noise in the clusters of high rises which house millions in the South Korean capital.

For new homeowners, the jarring reality of daily life involves some kind of unwanted audio accompaniment.

In Wall to Wall office worker Noh Woo-sung (Kang Ha-neul) is driven to distraction by noisy neighbours.

After pooling together all his money to purchase a much sought after apartment everything turns sour.

In the space of three years, he is mired in debt and has called off his marriage.

The 84 square metre – the film’s Korean title – paradise is now a rubbish strewn hovel with empty soju bottles and ramen cups all over the floor.

Worst of all Woo-sung is plagued by the sound of a vibrating phone and footsteps which wake him up at 4:30am every morning.

As his money problems escalate, he takes a part time job delivering food, yet everything spirals out of control as the irritating noises exacerbate.

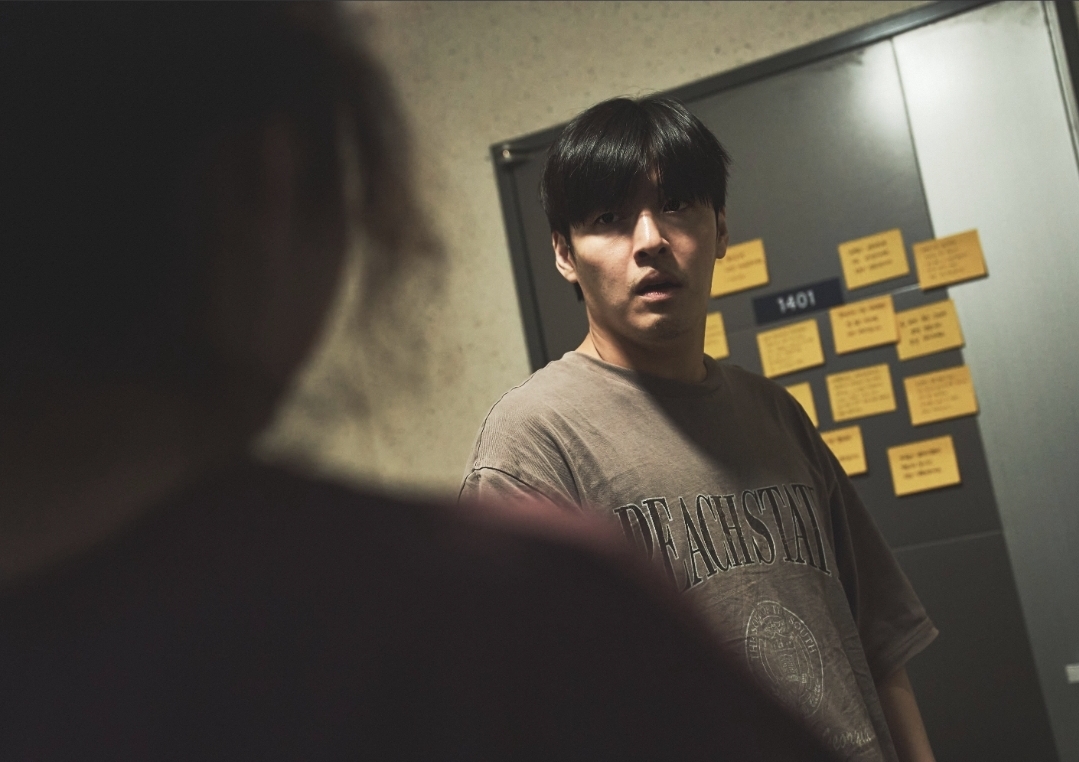

Unit 1401 becomes almost unliveable for Woo-sung, who is initially blamed for making a racket by his downstairs neighbours. They pin a flurry of Post-it notes on his door saying he is disturbing their school age children and that the sounds are only audible when he enters the apartment.

Woo-sung takes it into his own hands to find out the source of the annoying noises but finds no easy solutions as all his upstairs neighbours, including the intimidating Young Jin-ho (Seo Hyun-woo), deny responsibility.

Former prosecutor turned resident representative Jeon Eun-hwa (Yeom Hye-ran) acts as peacemaker from her penthouse apartment, yet the unbearable sounds continue leaving Woo-sung utterly exasperated.

The tension between floors reaches a breaking point as everything builds to a turbulent crescendo.

Although the identity of the noisemaker becomes progressively clear, director Kim Tae-joon craftily uses misdirection to lead us off the trail.

The culprit emerges as the action amplifies after the half-way mark of a film which forcefully portrays a man whose dreams disintegrate into noisy nightmares.

Stark aerial shots depict the enormity of the concrete sea in a jam-packed metropolis where more than 60 percent of people live in apartments which barely conceal any noise from neighbours.

In a vivid dream sequence the walls of Woo-sung’s apartment crack apart as a cacophony of hellish sounds shatter his ear drums.

The upstairs downstairs Argy bargy would be barely audible without the striking performances of the central three characters.

Kang Ha-neul is building a reputation as one of the finest actors of his generation and is incredible as the demoralised Woo-sung.

In a wide-ranging performance full of plausibility and pent-up frustration he carries the film alongside the underrated Yeom Hye-ran who brilliantly plays a character with a veneer of respectability that masks a much darker side. As the enigmatic, tattooed upstairs neighbour Seo Hyun-woo cuts a menacing figure as the outwardly calm Jin-ho.

Despite its embellished depiction of a genuine problem, director Kim Tae-joon does capture several real-life aspects of an aggravating modern-day phenomenon.

While it might appear far-fetched there have been many cases of full-blown neighbourly disputes with some resorting to take revenge by playing loud music or construction noise using high tech speakers.

Even the beeping sound when people open and close their apartment doors – using keypads with numbered codes instead of physical keys – can be infuriating.

Shouting, tapping, thudding, and banging are all too common in hastily constructed buildings with paper thin walls.

Although I didn’t live in a high rise in South Korea, parts of Wall to Wall were familiar to me.

A downstairs neighbour consistently woke me up in the early hours of the morning for weeks in my small two room flat in Dongtan, Hwaseong-si (an hour south of Seoul) and despite repeatedly stomping on the floor the tapping sound didn’t stop.

Flashy advertisements detailing the benefits of new apartment buildings are everywhere in South Korea from posters on bus shelters, to subway stations and in the numerous estate agents in every town and city.

Everything is bigger, better, swankier, and more desirable.

At least that’s what they want people to believe. Wall to Wall depicts an alternate reality to the one heavily promoted in new apartment developments in the land of kimchi, K-Pop, and everything else starting with the letter k.

As part of Netflix’s ongoing commitment to show Korean films – I still prefer going to the cinema – – it’s an effective thriller which rams home a noisy message of fractured lives behind the concrete facade.

@skasiewicz.bsky.social